October 15, 2022: Parashat Bezot Haberachah – Unification Through Messiah

This week marks the last weekly portion in the Torah: Deuteronomy 33–34. Join David as he unwraps "this blessing" (bezot haberachah) by Moses before his death, a blessing grounded in unification – unification made more real for us in Messiah.

Follow along in the AUDIO PODCAST, by clicking on the play button below, and reading along with the notes, as you listen to today's Parashah:

Here we are in the final parashah of the Book of Deuteronomy, and the final parashah of the Torah. For virtually the entire Book of Deuteronomy, right before his death, Moses spent most of his time admonishing the Children of Israel, using harsh language towards the people, reminding them of the importance of loving Hashem, listening to His voice and cleaving to Him. So, what a way to end off the Book of Deuteronomy and the entire Torah with a parashah titled “Bezot Haberachah”, which means “And this is the blessing”. Not just “a blessing”, but “הַבְּרָכָה”, “the blessing”.

And so we open the parashah to these words in Deuteronomy 33:1:

וְזֹ֣את הַבְּרָכָ֗ה אֲשֶׁ֨ר בֵּרַ֥ךְ מֹשֶׁ֛ה אִ֥ישׁ הָאֱלֹהִ֖ים אֶת־בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל לִפְנֵ֖י מוֹתֽוֹ׃

“And this is the blessing with which Moses the man of God blessed the Children of Israel before his death.”

The last time the tribes were blessed in such a manner was when Jacob blessed their tribes’ namesakes – his sons, right before he died. Jacob’s blessing (found in Chapter 49 of Genesis) opens with some interesting words (Genesis 49:1-2): “Then Jacob called for his sons and said, ‘Assemble yourselves and I will tell you what will befall you in the End of Days.”

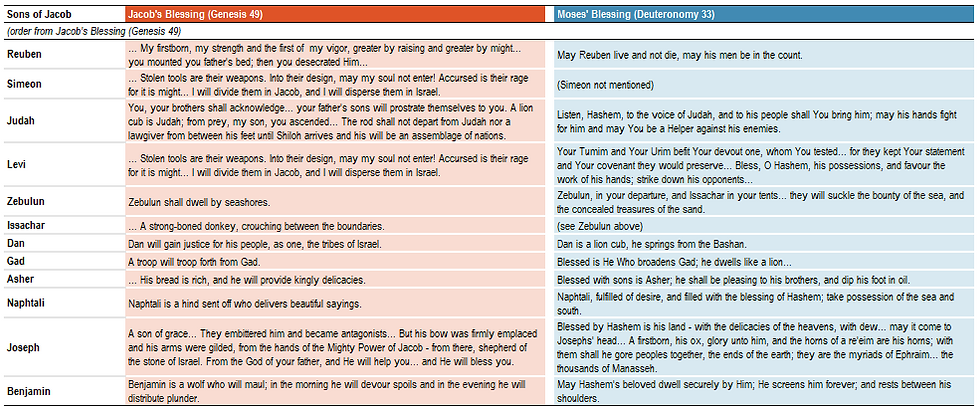

However, upon reading through the blessing for Jacob’s 12 sons, you don’t find much on what would befall them in the End of Days. Really, the only son’s blessing that atleast casts some light at all in this direction is for Judah, where we read some Messianic words (we will revisit this later). Otherwise, the other sons’ blessings were either words of chastisement (for Reuben, Simeon and Levi), highlighted character traits (Zebulun, Issachar, Dan, Gad, Asher, Naphtali and Benjamin), and words of abundant blessing (for Joseph).

Referring back to Genesis 49:1, remember Jacob’s first command to his sons: “Assemble yourselves”. These are the words that came before Jacob uttered the words “and I will tell you what will befall you in the End of Days.” At this point, the 12 sons were not in an “assembled” state – meaning, they were not yet functioning in a state of togetherness, and as such, Jacob could not reveal what would befall them in the End of Days in the entirety of which he would have liked to reveal. This is revealed through the varying blessings that were given to them – some were good, some were “status quo”, and some were reprimands. As Jacob commanded them in his first words, his 12 sons were to assemble themselves.

Returning back to this week’s parashah, I look at Moses’ blessing for the 12 tribes as a “reassessment” of Jacob’s blessing. On his death bed, in the land of Egypt, before his descendants would enter into exile there, Jacob blessed his 12 sons with an eye to what they could and would become. Several hundred years later, Moses led the descendants of those 12 sons, who were now an abundant nation of people out of exile, and were about to enter back into the Land of Promise. They had come full circle. And it was here on the Plains of Moab, and at the end of the Torah, that Moses “reassessed” the blessing on the tribes.

In Deuteronomy 33:4-5, Moses reiterates words that were spoken by the people before Hashem: “’The Torah that Moses commanded us is the heritage of the Congregation of Jacob.’” Moses continues on speaking about Hashem: “And He became King over Yeshurun when the numbers of the nation are gathered – the tribes of Israel in unity.”

First, in Verse 4, Moses uses the term “קְהִלַּ֥תיַעֲקֹֽב” “Congregation of Jacob”, a unique term that you don’t find used elsewhere. [You do find the root noun “קְהַל” used in a number of places, and in some cases, used by Hashem in speaking to Jacob about his descendants (Genesis 28:11, 35:11, 48:4), but not the term “Congregation of Jacob”].

Second, is Moses’ use of the term “ישֻׁר֖וּן” “Yeshurun”, which is only found three times in the Torah (and a fourth time in Isaiah 44:2), all spoken by Moses in Chapters 32 and 33 of Deuteronomy. “Yeshurun” means “Upright One”. What is the point being made here? That of “unity” – the name “Yeshurun” is used for the Congregation of Israel when all of the 12 tribes are dwelling in unity with each other.

Moreover, the term “Congregation” is more than just the nation of Israel, otherwise common terms like “House of Jacob”, “seed of Jacob” or “Children of Jacob” would have been used. Rather, “Congregation” includes the descendants of Jacob as well as all of those who choose to join Israel. In other words, when Jacob gave his blessing on his 12 sons, he spoke just the right words for each son that would point each son in the right direction, whether it was to challenge one, motivate another, inspire yet another, or commend another – all with the intended purpose of bringing them into a state of unity. Similarly, before Moses was about to give his blessing on the 12 tribes, he spoke of the importance of the tribes being in a state of unity – that only through unity would they inherit the name “Yeshurun” or “Upright One”.

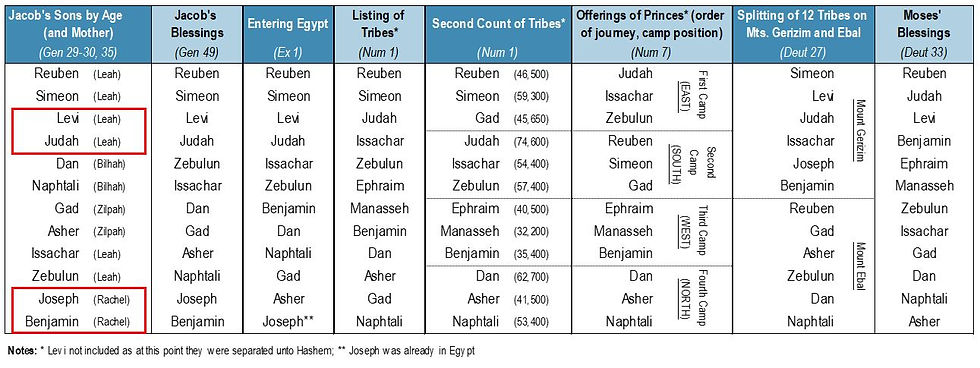

And so, in similar fashion to Jacob, Moses’ blessing for each tribe varied based on what that particular tribe needed to hear. As you compare the blessing of Moses to the blessing of Jacob, you notice several things: 1) The order of the sons or tribes of Jacob changes; and 2) Some sons receive elevated blessings, others remain more or less the same, and one is missing.

Regarding the order, it appears that it is in part based on the geography of the tribes in the Land, moving from west to east and south to north. Hence, Reuben was first as he requested some of the land east of the Jordan, and was situated furthest south. Next was Judah, situated west of the Jordan and in the south. Levi did not have a portion in the Land, but rather lived in cities scattered through the other tribes (more on this later). Then came Benjamin who was situated north of Judah. Joseph was next, and included Ephraim on the west side, and Manasseh on both sides of the Jordan (remember, Joseph received a double portion inheritance that went to his two sons Ephraim and Manasseh). Then came Zebulun and Issachar, situated more northward on the west side. Gad was the last of three tribes on the east of the Jordan. Finally, came Dan, Naphtali and Asher situated most northward on the west side of the Jordan.

Regarding changes in the blessings between Jacob and Moses, the most notable change is that of Levi, who was chastised by his father Jacob, but elevated in his blessing from Moses. Furthermore, Simeon – who was chastised along with Levi by Jacob – is not named by Moses at all. Going back to the point made above on geography, Simeon along with Levi did not have a portion in the Land and as such dwelled in cities within Judah. This is likely the reason that Simeon was not mentioned. Similarly one could ask, why was Levi not mentioned as well seeing that Levi lived in cities throughout the entire Land? As mentioned earlier, the tribe of Levi was elevated in their blessing from Moses. Why? Because Hashem consecrated them to an elevated status amongst the nation because they proved themselves worthy through their actions at Mount Sinai regarding the Golden Calf and throughout their service to Hashem for the 40 years of the Wilderness. You could also say that the merit of Moses, Aaron and Miriam – all from the tribe of Levi, had a role to play in elevating the tribe as well. Finally, while Jacob’s blessing for Judah took on a strong Messianic tone, Moses shifted the Messianic blessing to Joseph here.

One other interesting observation is that of Moses placing the blessings of Judah, Levi, Benjamin and Joseph next to each other. First, Judah’s descendants would bring forth the kingship of Israel. Second, Levi held the title of priesthood for the nation. Third, Benjamin shared a portion of the city of Jerusalem and the Temple within its borders (Joshua 18:21-28), and was also the only other tribe with a portion in the Land that remained with Judah after the division of the nation under Jeroboam. And finally, Joseph (most notably through his son Ephraim’s portion) held within its borders the site of Shechem and Mounts Gerizim and Ebal – the location that stood for the unity of the nation (see my previous teaching on Parashat Ki Tavo for more on this). Afterward, Moses blessed the remainder of the tribes, highlighting their key qualities as they pertained to the Land.

With unity in mind, why is it important to focus on these 4 sons of Jacob (Judah, Levi, Benjamin and Joseph)? They represented two of the oldest sons (by Jacob’s wife Leah) and the two youngest sons (by Rachel).

Regarding the older, the first two sons by birth – Reuben and Simeon – lost the privilege of leadership. They were chastised by their father Jacob, and moreover, they did not do anything notable throughout the 40 years in the Wilderness to elevate themselves (unlike Levi). The next two sons in line after them were Levi and Judah. The two younger sons, Joseph and Benjamin, were the only two sons by Rachel, and the favourites of Jacob. Not only that, but Joseph proved himself through his actions in Egypt – by keeping himself grounded in Hashem, and remaining humble throughout all the sufferings and hardships he faced to recognize that it was all part of Hashem’s plan for the future of the nation of Israel. So, to summarize, these 4 brothers had an important part to play in bring the nation together in a state of unity.

The most notable factor of unity, of course, has to do with the Messiah. To quote Jacob’s blessing for Judah in Genesis 49:10: “The rod shall not depart from Judah nor a lawgiver from between his feet until Shiloh arrives and his will be an assemblage of nations.” The word “Shiloh” could be interpreted as saying “his” as in “the kingship is his”, undoubtedly a Messianic reference. We know that the Messiah would come from the tribe of Judah, later through the lineage of King David (2 Samuel 7:12-16, Isaiah 11:1, Jeremiah 23:5-6). And what is the Messiah’s prerogative? An assemblage of nations. Ultimately, that the Messiah would rule as King over an assemblage of nations.

In Moses’ blessing for Joseph in Deuteronomy 33:17, he says: “A firstborn, his ox, glory unto him, and the horns of a re’eim are his horns; with them shall he gore peoples together, the ends of the earth…” This is also a Messianic reference. A “re’eim” is believed to have been a large ox with large horns. The act of “goring” peoples together is not in any way to be misconstrued as a violent act, but rather as a means to forcibly bring peoples together from the ends of the earth. Surely, we know that the Messiah was prophesied to come from the tribe of Judah, so why a reference to the Messiah from Joseph? Because it is not necessarily to be taken that the Messiah has any blood connection to Joseph, but rather that the Messiah carries the traits of Joseph. Just as Joseph suffered at the hands of his brothers – an act of baseless hatred – being sold into slavery into Egypt, so the Messiah would be subjected to the same conditions.

We find the prophet Isaiah writing numerous times about the Messiah as “a suffering servant” – in Isaiah 42:1-4, 49:1-6, 50:4-7 and 52:13-53:12. Through Joseph overcoming his suffering, he brought security, abundance and unity to his family, and provided the necessary foundation for his family to become a great nation. Similarly, the Messiah’s elevation would cause a mighty act of unification on a much greater scale – for the entire world. Either way, as a direct descendant of Judah or as a spiritual descendant of Joseph, the Messiah’s mandate would be to unify the world.

Finally, why Levi and Benjamin? As mentioned previously, Levi carried the priesthood and Benjamin’s portion in the Land partially housed the Temple (shared with Judah). Both are connected. Remember, the priesthood was not just some ceremonial function. The priesthood was consecrated to Hashem, and they were the role models for the nation – for the people to look to and to replicate in order to learn how to live a consecrated life to Hashem as well. This didn’t mean performing the acts of the priesthood (for this was forbidden), but rather to connect with the deeper significance of the Levite and Kohanim service – that every part of their priestly service revealed a different element of living a consecrated life to Hashem. And where was the service performed? But of course in the Temple, the most sacred, holy place on earth that was situated in the land portions of Judah and Benjamin. As the priesthood functioned as spiritual leaders for the nation, the place they served in was the Temple. As such, their function and the location of their function were unifying factors for the nation.

With all of that said, we can now turn to Yeshua, who is that same Messiah that was prophesied by Jacob in Jacob’s blessing over Judah, and again by Moses in his blessing over Joseph. Of course, the entire Messianic mandate has not yet been fulfilled, that is a given, and as such, the final unification of Israel and the nations of the world has not yet happened. This is yet to come. However, Yeshua came as a suffering servant to the nation of Israel. Just like Joseph, there was baseless hatred against Yeshua for he was not recognized in the way he was expected to come – as a reigning King to sit on the throne of his forefather King David. As a result, he was killed, but overcame the grave to be resurrected to life and to be elevated to the right hand of the Throne of Hashem. This is very important because what Yeshua accomplished on earth was to lay the groundwork for the completion of the Messianic mandate when he will return. What was that groundwork? To unify his 12 disciples – a microcosm of the 12 tribes of Israel, and to prepare and empower them to reach their fellow Jews within the borders of the Land of Israel and beyond the borders to Jews scattered across the Diaspora, as well as to non-Jews who were drawn to the message of unification to Hashem.

Paul wrote in Romans 11 about the “baseless hatred” towards Yeshua, and how this would translate into salvation for the non-Jews (Romans 11:11-12, 15): “In that case I say isn’t it that they [Israel] have stumbled with the result that they have fallen away? Heaven forbid, quite contrary! It is by means of their stumbling that the deliverance has come to the non-Jews in order to provoke them [Israel] to jealousy. Moreover, if Israel’s stumbling is bringing riches to the world, that is, if Israel’s being placed temporarily in a condition less favoured than that of the non-Jews in bringing riches to the non-Jews, how much greater riches will Israel in its fullness bring them? … For if their casting Yeshua aside means reconciliation for the world, what will their accepting him mean? It will be life from the dead.”

So what are we to take from all of this? The blessings of Jacob and later of Moses have reverberated throughout all of Scriptures – from the Torah to the Books of the Writings to the Books of the Prophets to the Brit Chadashah (“New Testament”) and throughout the remaining 2,000 years of history to today. The Word of God is living, breathing and reverberating, as what was spoken and written thousands of years ago is still playing out today. Just as the message of unification was imperative on the Plains of Moab as the nation was preparing to enter the Promised Land, it was just as imperative during the days of the Kings of the nation of Israel, it was just as imperative at the time Yeshua walked the earth, and it is just as imperative today.

We as human beings seem to have a problem with the concept of unification though. We seem to unify around ideas of common thought, but only for a time and only until the efforts become adulterated. Our manmade efforts at unification always fail, and history speaks for itself, regardless of what nation, ethnicity, culture or religion. The reason that the role of Messiah was and is critical in the two blessings is because the Messiah is the only way through which the nation of Israel can be unified. More than that, it is only through the Messiah that the entire world can be unified.

This is not just about unifying under a common banner to form the perfect earthly kingdom ruled by man under the dictates of man – rather, this is about unifying under the banner of the Kingdom of Hashem through his emissary Messiah Yeshua who will one day return as King Messiah to bring about the ultimate and perfect unification of Israel and all of the other nations of the world. The good news is that it will one day happen – the Messiah will return to complete what he started, to complete the unification process, to fulfill all that has been written in the Torah. Until then, may we continue to remain focused and connected on sharing the good news – the message of unification through Yeshua to others – to the Jews and to all other nations… to the ends of the earth.

Before Yeshua was elevated up to heaven, he spoke to his disciples these words (Matthew 28:18-20): “All authority in heaven and in the earth has been given to me. And you, go to all the nations. Make disciples; immerse them for the Name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and teach them to keep all that I have commanded you. And see, I am with you all of the days until the end of the age.”

Amen.

Comments